This Republic of Suffering: Good deaths

This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War is an overview of how Americans managed death, in response to a larger and more sustained barrage of it than anyone could have previously imagined.

Written by historian (and Harvard president) Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic is a hybrid of popular and academic history, and its citation style is occasionally rote — assertion; primary source, secondary, primary, rephrase; repeat — but structuring the book like a traditional thesis or paper is the best way to confront its vast, implacable subject. It parallels the ways Americans found to confront it, even down to the chapter headings (“Burying,” “Naming,” “Realizing,” e.g.).

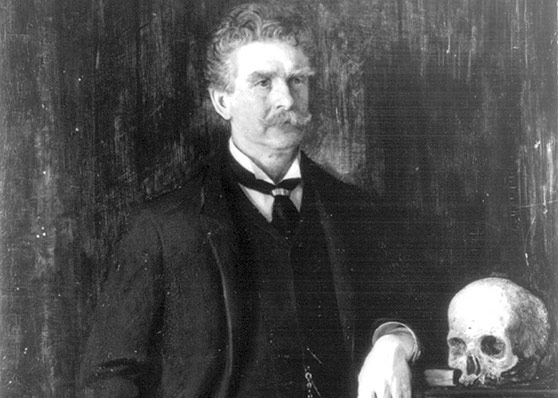

Faust’s writing is excellent, setting a brisk but not disrespectfully rushed pace, and she doesn’t get bogged down in establishing ownership of any one waterfront; completism isn’t what’s called for her, and she smartly doesn’t try for it. Often, dozens of sources support a point about, for example, the “concept of the Good Death” — ars moriendi — that Victorian Americans counted on to bring order to the chaos and grief of the end of life. Other times, Faust follows a single source: the men tasked with “repatriating” Union dead to the national cemeteries; Ambrose Bierce, whose “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” is legendary, and typical of how his wartime experiences tinted his writing with bitterness and horror ever after.

That balance is very readable, stale-proofing the prose and letting Faust play some deep cuts that even those with extensive grounding in the topic might not have heard. I didn’t know anything about ars moriendi; I didn’t know that, “as late as the first decade of the twentieth century, fewer than 15 percent of Americans died away from home” (9), hospitals then considered a place for “the indigent, not respectable citizens,” to die; I didn’t know George McClellan’s maddening (to Lincoln, for one) aversion to engaging the enemy on the battlefield stemmed from an “aversion to killing” that makes him both more sympathetic and simply unfit for command. I didn’t know much about Bierce, either, and Faust’s description of his background and carefully selected passages of his work made me want to dig into his collected writings immediately:

Bierce was the tenth of thirteen children — all given names beginning with A — born to parents he seems to have despised. He enlisted in the Union army when he was only eighteen. … Bierce’s writings about the war are preoccupied with the gruesome and the macabre and display what seems almost an eagerness to transgress proprieties of thought and representation. (196-7)

A detailed comment by Bierce about a man dying from a shot to the head, almost fetishistic in its hideous details, follows.

Faust is also very good in the aftermath, the portrayal of the vain attempt by quartermasters, War Department historians, and bereaved fathers to get arms around the sheer volume of death and waste. One man records each demise he can confirm, savoring the “peculiar” deaths as humanizing the mass: kicked to death by a mule, another bitten on the thumb and then exsanguinating after the infected digit was amputated, another “died of poison while on picket, by drinking form a bottle found at a deserted house” (261). You can see the devoted officers, leaving their wagons piled high with empty pine boxes to slosh into May mud and forgotten woods, to count every man and bring him home. This Republic isn’t candy-colored fun by any means, but it isn’t depressing, either; like some funerals, it both mourns and celebrates. An informative read with bracing illustrations, good for all levels of grounding in the topic. Straight A.

Tags: Ambrose Bierce books Drew Gilpin Faust George McClellan

My daughter had to read this last school year. She was in junior high. I skimmed through and found the chapter titles chilling but straight forward. She is a history buff already and she enjoyed this book.

I think this was adapted for PBS; maybe an American Experience episode. I was glued to the couch. You are right – it both mourns and celebrates and explains so much about how we feel now about these subjects. I’ll have to read the book now!

I read this last summer, I enjoyed it quite a bit. I too had no idea about the Victorian idea of the “good death.” It’s amazing how what was once such a strong part of American culture just faded away.

This sounds fascinating! Once I get the “so huge it’s gone beyond pathetic into hilarious” books-to-read pile down a bit, I’m adding this to it.

I recently discovered that we had not only the print version, but the book-on-CD version of this in the library in which I work – so I immediately borrowed the latter. It was SO good. Thanks for the review, which is what brought it to my attention! A perfect way to observe the 150th anniversary of the Civil War (along with “This Mighty Scourge: Perspectives on the Civil War” by James McPherson, and the Great Courses Series “The American Civil War” by Gary Gallagher – all 24 discs of it!). Damn you, Civil War- you’ll turn me into a history buff yet!