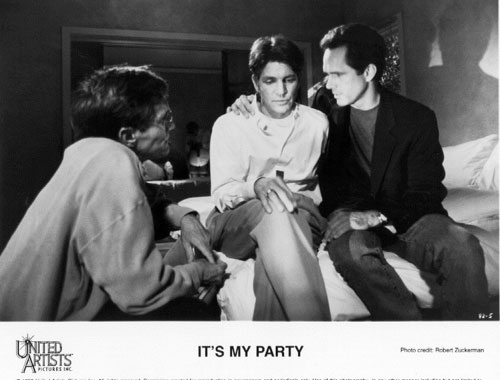

It’s My Party

A cable channel I watched frequently in the mid-nineties — I don’t remember which one; probably HBO — got the rights to It’s My Party, and the repellent promos, in which a woman simpered “it’s muh par-teeee” over a montage of Eric Roberts smiling bravely through imminent tears, turned me off the film for years.

It didn’t enjoy positive contemporary press, either; Roger Ebert liked it, but few of the other reviews gave the movie much credit, and that only grudgingly. Marjorie Baumgarten, writing for the Austin Chronicle, seemed surprised to have liked it at all: “Despite the movie’s frequently lame dialogue, ill-developed characters, cheap melodramatics, and avoidance of any difficult right-to-die issues, there is still something compellingly real about It’s My Party.”

I felt the same way. The acting is all over the place, by turns amateurish (Olivia Newton-John), cartoonish (Bronson Pinchot), and clashing with the material (George Segal). Eric Roberts, cast against type, is unexpectedly outstanding, but his performance is undermined by Gregory Harrison’s silent-film deer-in-headlightsing in the ex-lover role; every emotion he expresses, or tries to, is overlaid with a veneer of the terror he so obviously feels at the prospect of the future scene in which he and Roberts will have to french.

The writing doesn’t help him, in fairness. Almost everyone has a lot of heavy dialogue…heavy in the way that wet toilet paper is heavy. The idea has a lot of potential, but its specifics — a man who has entered a terminal stage of AIDS decides to throw himself a goodbye party, then kill himself at the end — lead to strings of unmediated clankers like “I wonder which is braver: taking a life, or not taking it.” There is no discussion, no reference, that is not hopelessly on the nose.

But the nose does have its uses. Among the tedious histrionics, the movie has positioned a few sweetly awful moments that get you thinking about what this party is like to attend in real life (and the film is evidently autobiographical). I have gone to a man’s house for the last time, knowing that I won’t see him alive again; we all have made a variation on that visit. It’s the longest driveway of your life, and you dread the first step. At times, the movie gets that right, the not wanting to turn your back, the running out of “see you later”s. During those moments, I thought to myself that it’s just as well the rest of the movie is not so great, even laughable (the Lon Chaney makeup on Christopher Atkins in his character’s death scene is so crude, it’s almost offensive). You can’t stand at the top of that driveway for 98 minutes. It’s too much to take.

It’s My Party is also instructive as a period piece of sorts, and I don’t mean the shoulder pads on everyone. As Nick reviews his cross-shaped art installation, fashioned from pictures of his many friends who have died of AIDS, I remembered how we thought about AIDS then. The movie came out in 1996, which seems like the time that the diagnosis stopped signifying an absolute, non-negotiable, short-date death sentence; the transition had begun, I think, into considering it a manageable chronic condition. Nick isn’t ending his life because of the diagnosis itself — he has lesions on his brain that may kill him within the week, and will certainly render him non compos mentis — but I for one forget sometimes the way it terrified us. Terrorized us, really. Laid waste to people, literally and figuratively.

“Should” the movie have dug deeper into right-to-die issues? I suppose. But in 1996, in a movie written by a man who attended that very party hosted by his dying partner, maybe it seemed to go without saying — which is just as well, because a script that thinks “When you got sick, I guess I got scared” makes up for Brandon kicking an ailing Nick out of the house they shared and keeping the dog is likely not up to the task.

…I know. A lot of the movie is…that, but then it gives you the goodbye scene between Roberts and Pinchot, which is so clanky and odd that it feels true, so it’s worth checking out.

Tags: Bronson Pinchot Christopher Atkins Eric Roberts George Segal Gregory Harrison Marjorie Baumgarten movies Olivia Newton-John Roger Ebert

Roberts has been good — even outstanding — often enough that it never comes as a surprise to me when I catch him really on his game in something. It’s been a strange career…actually two careers, which don’t match up. This is an actor who, in his twenties, was excessively choosy, appearing in only six theatrical films (all of them, to some extent, interesting and worthy) between 1978 and 1985. Then he got the Oscar nomination for Runaway Train, and turned 30, and everything changed. Suddenly he would be in anything and everything, and a lot of it was terrible; and when the material encouraged the worst in him, he would lower himself to it obligingly. But if you see him in It’s My Party, or Star 80, or the unjustly forgotten Raggedy Man, you can see why the smart people were once talking him up as The New (Brando, Newman, whoever).

My suspicion is that his well-documented personal problems (of the substance and legal natures) eroded his discernment, and kept him from becoming the great he might have been. However, in the sense that many people believe he can *only* do overwrought ticfests, or treat him as a “Julia’s brother” punchline, he’s underrated.

Personally, I love this movie, and where some critics saw “ill-developed charcters” I saw a deliberate refusal to overlay the script with lots of clunky exposition explaining the backstory of all these people-they are friends and relatives, we don’t have to know exactly what the relationship is to understand the situation. Plus, with a cast that large, not everyone is going to be fully developed in a two hour movie-that’s not the point. The point is Nick’s story, that he’s saying goodbye to the people that love him.

The only character who truly got short shrift was the Catholic who’s there as the movie’s cursory examintion of the moral right to die question. But the script writers are obviously on Nick’s side, so they give short shrift to the opposition-they would have been better off to not attempt the right to die argument at all, and just to present Nick’s choice as a moral certainty.

To be fair to ONJ, she is saddled with one of the worst pieces of dialogue in the film-that “I think Nick is lucky” speech. He’s dying of a horrendous disease. The hell? Regarding Harrison…I don’t see that. I see he’s going for a guy who’s guilty as hell/scared/unsure of how to act or what to say in light of their history.

Hold up — how is it autobiographical when the main character commits suicide?

I see he’s going for a guy who’s guilty as hell/scared/unsure of how to act or what to say in light of their history.

I’m sure that’s what he’s going for. What he’s giving is more like “Keanu eats a bug.” In his defense, the script insists on repeating the “Nick doesn’t want me here, I’m leaving”/”no, don’t go” dance, not Harrison; the character is tough. But so is Roberts’s, and he manages to find the truth in it. Harrison seems overmatched. A comparison to Angels in America probably isn’t fair to anyone, but if you’re going to attempt that storyline, you have pretty weighty company.

You’re right about ONJ. She’s also carrying exposition water for the father-son-reconciliation B-plot, which is hard to do well. (See also: Margaret Cho, who has at least four “look stricken; get folded into a hug” bits.)

I forget what movie I said this about…maybe Crossing The Bridge…but when the material is autobiographical, sometimes the director has difficulty choosing narrative flow over “but it really happened just like THIS,” and I think that’s part of the movie’s problem. With that said, when it works, you really see that it happened just like THIS.

@Jen B.: He…wasn’t the main character. His partner died and had a party like this, apparently.

I don’t think they were broken up, either, but I’m not sure “autobiographical” requires it to be a reenactment.

This movie strikes way too close to home for me. My father passed away from AIDS in 1996 so it took a really long time for me to watch it. And, even now, I don’t think I have watched it all in one sitting – parts of it one time, parts of it another. But the goodbye scenes struck me as very real, even in their clunkiness, because that’s what those scenes are really like. Granted, it can be argued that that’s the difference between movies and real life – movies have an opportunity to smooth over the rough edges of real life. But I think at the time this was made, there was an aversion to smoothing over those edges. So much of AIDS, up until the mid 90’s, was swept under the rug that there was a real desite to show “Hey, look, this is what we’re going through.” Unfortunately, that often makes for a disjointed movie.

For our part, my father insisted we have no funeral, just a party a few years after he had died. Which we did, on St. Patrick’s Day, five years later. A good time was had by all.

If you re-watch And the Band Played On, it has a similar aspect of reminding what it was like in the 80s and early 90s. In some ways we’ve come so far, and in others, it’s like we’re treading through tar.

Heh. God, the eighties. One of those times where it’s great to be a rich white straight man but it really kind of sucks if you’re anyone else.

I remember Hunter Thompson’s oft-repeated refrain; the eighties was the time when sex was death, rain was poison, and the President of the United States thought that the world would end soon.

Remember when sick kids and their families were burned out of their homes? When kids weren’t allowed to go to school for fear of spreading the infection? It seems like centuries ago, and now AIDS is such a familiar part of the landscape it’s difficult to think of it even as a problem, much less a plague, which is what it is.

Nothing seems more “dated”/timelapse photography than watching the evolution of our (as in first world, USA) response to something like AIDS, especially through our art. But it shouldn’t seem dated, as in “wow, can you believe those crazy olden times?” It should seem like photographs, as in “Believe it, kid.”

Internet serendipity strikes again–I am directing “Angels in America” in the fall and just this morning was doing some reading (of the script and some essays). I made myself a note to do some serious dramaturgy for the cast because actors who are the right age for Louis and Joe and Prior may not remember that time you’re describing–when AIDS seemed to be an automatic death sentence, one accompanied by months or years of infections and medications and dashed hope. I’ll need to watch this, I think. Thanks.

Our cultural memory is astoundingly short. Be it AIDS, the cold war, the need for civil rights protections – “the kids these days” do not know about these things unless they’ve gone deep into scholarship about them, much less understand the emotional feel of the times. Admittedly, it is hard to get the feeling unless you were there, and you can’t help when/where you were born, but that’s what art strives to communicate.

I ended up getting a second bachelor’s degree when I was 10 years older than the normal-aged students – 10 years ago – and they had no idea what Socialism was, and describing it in terms of the Communism-Capitalism axis (as we were taught to do in the 80’s) didn’t help because they had never been exposed to those things as anything but tags for good and bad guys.

My M.Div., multilingual, globe-hopping brother couldn’t understand my casual reference to World War resonances in The Lord of the Rings and had to have “Europe was devastated by the World Wars, and a huge chunk of English literature since 1915 or so either directly or indirectly addresses that, especially the literature between 1920-1960,” spelled out – and he still has no idea, really, because his entire exposure to that slice of history came in the 2 weeks before the end of school in 1989, and was presented, a la The Simpsons, as “We won!” and “It was great and we’re all better for it, woo!”.

Plenty of people my age I’ve talked to don’t get that things like freaking Godzilla and Akira are responses to the atomic bomb, even though that’s flat-out stated in the dialogue, and that, hey, maybe Japan has some issues to work out because of the whole bombing thing, and maybe that’s going to come through in its art?

Even this morning, for the stupidest of reasons, I came upon shortcomings of my own – I was transferring the contents of one purse to another, one of those ridiculous, delicious semi-translucent candy-colored vinyl things from that one summer, you know, when was that, huh, I remember some companies required clear vinyl purses and backpacks to prevent carrying in guns because of, um, wasn’t it a response to Columbine, or was it Oklahoma City, and that was when, um, 1995? Wait, wow, the 90’s were pretty terrorism-filled, weren’t they, yeah, I remember that atmosphere…etc. If I can’t remember specifics better than that, with my interests and obsessions, expecting some poor kid born in 1990 to have a handle on everything is pushing it. Still, there’s nothing wrong with increasing the encouragement for everyone to TRY. (And it’s not like artistic media don’t give you plenty of chances – Cold Case and Quantum Leap and Dr. Who and re-runs of sitcoms from the last 60 years are pretty accessible, and just reading good mystery novels can give you lots of insight into the history and attitudes and mores of past times – and then there are the other novels, and drama, and music, and visual art, and…)

I mean, the world is huge and history is long and nobody understands everything, but there are some big milestones everyone needs to understand, and you should at least be responsible for things that happened during your life.

Rant over.

And now that I sound like a completely pedantic crashing bore, I suggest that if you can find it, watch a thing called “What If I’m Gay?”. It was a “CBS Schoolbreak Special” thing made in 1987, it’s extremely well-intentioned but unintentionally hilarious, and it does represent 1987 pretty well. I found it on a VHS tape I have no idea how I came to own.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0339895/

Just look at that cast!

@Liz: I prefer the one where Scott Baio’s best friend is gay (mostly because the best friend is cute).

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0156143/

@JenS Remember when sick kids and their families were burned out of their homes? When kids weren’t allowed to go to school for fear of spreading the infection? It seems like centuries ago, and now AIDS is such a familiar part of the landscape it’s difficult to think of it even as a problem, much less a plague, which is what it is.

I remember when my uncles started getting sick and my mother told me it was AIDS they’d gotten through their blood transfusions for hemophilia but I wasn’t allowed to tell anyone because there might be some massive retaliation in my little bible belt town. I remember a a Sunday School teacher telling me that all people with AIDS were going to hell and breaking out in tears but not being able to tell a single person why that affected me for worries that my personal family drama would be found out and then be made into a town drama, so yeah. Different landscape back then. One I wish to hell we didn’t have to live through at all.

The Bloody Munchkin brings up another cause for cognitive dissonance around AIDS in that time (at least in my southern small town): the idea that AIDS was mostly something that bad people got for being immoral, but a few “innoncent” people got it from transfusions — I think (hope) we’ve come a long way from believing that gay men were inherently evil and being punished for their lifestyles.

[…] tomatonation.com […]

[…] tomatonation.com […]

[…] tomatonation.com […]