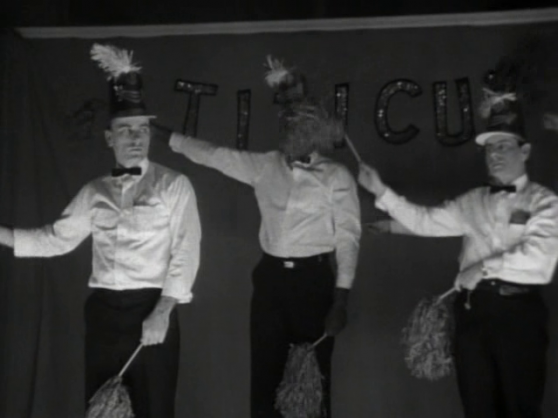

Titicut Follies

The pre-Nixon-era mental hospital is a preoccupying terror of U.S. popular culture to this day. This isn’t without basis; madness, and its attendant visions and rants, is a preoccupation of narratives throughout the world and since time immemorial. American stories explore and re-explore the tension between, and guilt baked into, competing reactions to the mentally ill: that we as a society should never have locked “them” away, but also that, once we had, we never should have let “them” out again.

The fictional attempt to resolve or clarify on film our visceral anxieties about these institutions tends to lead to Gothic fantasias: senseless assaults, canopies of Fincherian mildew, inchoate howling, fantastically gruesome lobotomies, photos with cosmetically burnt edges, abandoned bedsprings creaking in a breeze with no apparent source. And that’s just Session 9.

Titicut Follies provides a useful contrast, a crisp statement. The way its scenes unfold, at length, allows their details to emerge slowly from the sensory glare. Horror films recreating these mental hospitals try to replicate that glare, the more sensationally the better, to distance us from “them.” Frederick Wiseman, I think, asks us whether there is a “them.” One patient protests that he’s not getting any better in the hospital, and at first, you see his point, or at least agree. Wiseman lets the footage run, and at about minute six, seventeen identical iterations and non-logic jughandles later, it’s clear that this isn’t a discussion but a compulsion.

The guards nagging poor, naked Jim about keeping his room clean; the staffer who’s always singing and doing shtick, who looks like an illustration from a turn-of-the-last-century carnival game, whose eyes and smile, like those of the patients, don’t match up…the line between us and “them” seems faint and artificial.

Wiseman doesn’t push that point, or maybe he does so by standing pointedly back from it; forty-odd years later, the audience knows what brutalities to expect in the material, so it’s harder to assign intent. But we can assume a certain level of scorn from the final title cards.

End Title 1: “The Massachusetts Supreme Court has told us to say that X.”

End Title 2: “X.”

Tags: documentaries Frederick Wiseman movies Titicut Follies

Of the few 60s-era docs I’ve seen, they all seem to have an “authority is evil” vibe. My particular fave of that genre is Obedience, which deals with the Milgram experiments – classic (an interesting, though flawed, follow-up to it was 2010’s The Game of Death, which applied the core principles to media).

This reminds me of the book I Never Promised You A Rose Garden, where it’s stated that a small but noticeable minority of the attendants and nurses in the mental hospital where the story takes place are clearly fighting their own demons, and use their work to draw a mental line between “me” and “them”.

I saw this in college while it was still under the Massachusetts restraining order limiting its viewing to legal and medical professionals or students of same. (Of course, it probably defeated the spirit of the injunction when you got in by being one of 2,000 freshmen enrolled in the largest Psych class at Cornell.) That ban didn’t fully come off for more than 10 years after that.

It was gruesome, but I’d seen documentary footage unearthed (by Geraldo Rivera when a local WABC reporter) of similar atrocities at the Willowbrook facility on Staten Island, which led to other investigations of even closer-to-home facilities to where I lived at the time.

It’s not hard to see where so much of this current crop of inhumanity to our fellow humans is coming from; hell, I lived through almost two decades of it growing up.

I remember it being shown at my college, prior to the 1991 ruling. It was the only film showing for which students were required to tender ID, I’m guessing because it was being shown under the student exemption to the embargo. Deeply bizarre legal situation.

I was less disturbed by this one than by the Willowbrook footage. (Seeing Geraldo thisclose to tears of grief and rage may have been the most unsettling part.)

Unforgotten is a great documentary that deals with the things that went on at Willowbrook. Cropsey kind of touches on it too~a documentary into the ‘Cropsey’ legend (regional boogeyman legend, Staten Island area) that deals with a man who was responsible for a series of abductions and murders in the area and had worked at Willowbrook. It also goes into how after Willowbrook was shut down, not everyone was accounted for, and there ended up being people living on the grounds of the former institution.

It does a good job of showing the community’s need to purge or cleanse themselves of what happened at Willowbrook and subsequently with undocumented former ‘patients’ that fell through the cracks.

And I put patients in quotes because there was a very fine line between ‘patient’ and ‘inmate’.

Holy crap, Session 9! I thought I was the only one who’d seen that piece of dreck. My favorite part? David Caruso’s drawn-out, “Fuck yooooou!” So, so bad.

It was one of the few Caruso performances I didn’t hate, actually, but past that it was quite terrible.

It may be a more regional thing, since them we /they scenario was historically drawn on racially charged lines (yuck); the “Boo Radleys” were always treated as “mostly harmless” and are still roaming freely about Southern small towns. One girl moved here in high school, and was terrified when a man got in her car while stopped at a train crossing. While she freaked out, she got to the school and we said: “Oh…yeah. That’s Willoby. Don’t worry, he won’t hurt you.” My own family included, we tended to minimize exposure to any psychiatrist/legal intervention that might have mandated the institutionalization you are describing. Obviously won’t work for violent patients, but we were lucky, and remain so. I would never even want to think about abuse of someone not able to resist or even comprehend it.