Open: Meth and the Maidens

— by Todd K

Often when an autobiography makes pre-release headlines for its “shocking revelations” (in the case of Open, the big ones were Andre Agassi’s early-1990s mullet wig, late-1990s meth use, and lifelong hatred of tennis), the question the reader may ask is, now that I know those things, is there any point in reading the book?

In this case, the answer is yes, even if — like me — your interest in tennis is such that you recognize the big names and can put faces to most of them, but rarely sit through a match and would fail any quiz on the outcome of specific tournaments. (Or on the equipment. Skimming through this at the bookstore, I saw the sentence, “Nick, I tell him — I love my Prince,” and briefly thought Agassi was revealing something about his musical taste.)

Agassi’s collaborator, former Pulitzer recipient J.R. Moehringer, is said in the acknowledgements section to have graciously declined an authorship credit, but he surely is responsible for the actual prose. He gives Agassi an improbably rich and quirky vocabulary, but the basic tone usually feels right: frank, rueful, and tart. It would be impossible to write nearly 400 pages about a tennis pro’s 20-year career without occasional lapses into “and then I played” repetitiveness — a tennis player’s annual progression through tournaments is repetitious even by pro-athlete standards.

But Moehringer demonstrates that repetitive does not have to equal tedious; he’s heroic in varying his language and finding fresh angles for summaries of dozens of matches, and there is little in his descriptions that a non-devotee will stumble over. There are intriguing (though usually too brief) analyses of the strengths and weaknesses of opponents Agassi encountered numerous times, and/or those of special significance in his career. The most flattering — even awed — words are not for Agassi’s great rival and contemporary Pete Sampras, but for the younger Roger Federer, who emerged in the autumn of Agassi’s career.

Agassi’s father, Mike, is vividly described as a short-tempered, violent martinet/taskmaster determined to live vicariously through his phenom son, having been “failed” by Andre’s three older siblings — essentially Armin Mueller-Stahl in Shine with a customized, dragon-like ball machine rather than a musical instrument. The scenarios and patterns of victimization are familiar but no less convincing for that, and the “personal” portions of the book only intermittently recapture the gripping quality of these early chapters.

Less interesting is the material on Agassi’s two marriages, though the treatment of the failed one to Brooke Shields is admirable for its evenhandedness. Which is to say they both come off pretty badly — if she is self-absorbed and insensitive, he’s still the guy who made a big scene storming out of her Friends taping because she was licking Matt LeBlanc’s hand…in character, for a television show, in her occupation as an actress. One comes away feeling this was simply a match of two people who, perhaps because their schedules gave them a lot of time apart early on, were too slow to realize they enjoyed none of the same things and barely had sufficient conversational chemistry to date. (One of the book’s few thuddingly bad lines does fall in this section: “I even miss the eyeless, hairless African masks [on Shields’s walls], if only because they were there when Brooke and I didn’t wear masks with each other.”)

Less interesting is the material on Agassi’s two marriages, though the treatment of the failed one to Brooke Shields is admirable for its evenhandedness. Which is to say they both come off pretty badly — if she is self-absorbed and insensitive, he’s still the guy who made a big scene storming out of her Friends taping because she was licking Matt LeBlanc’s hand…in character, for a television show, in her occupation as an actress. One comes away feeling this was simply a match of two people who, perhaps because their schedules gave them a lot of time apart early on, were too slow to realize they enjoyed none of the same things and barely had sufficient conversational chemistry to date. (One of the book’s few thuddingly bad lines does fall in this section: “I even miss the eyeless, hairless African masks [on Shields’s walls], if only because they were there when Brooke and I didn’t wear masks with each other.”)

Second wife Stefanie (not “Steffi,” we learn) Graf gets a loving, nearly worshipful portrayal, of the “wise woman of few words” variety. She remains a figure of some mystery to the end (more so than Agassi’s coaches, trainers, close friends, et cetera), but that too is convincing; it meshes with what I know of her reticent public persona. There is a modest poetry in the book’s final paragraphs: these two retired greats, now parents, play a meaningless game of tennis, and for once Agassi does not want to be doing something else.

There are a few small holes in the content. Though Agassi is laudably candid about a great deal, he does not devote a word to the controversies over his alleged use of anti-gay slurs, both as on-court expletives in frustration and, at least once, in a more considered context (his notorious “as happy as a faggot in a submarine” comment at the 1991 French Open). When the authors introduce Shields’s television co-star David Strickland as a tertiary figure, and emphasize his and Shields’s close friendship and humorous rapport (and Agassi’s alienation/envy in the face of same, complete with resort to the dreaded “third [sic] wheel”), the reader expects them to follow through and devote at least a few sentences to Strickland’s eventual suicide (which occurred near the end of the Agassi/Shields marriage) and its effect on Shields. But once the friendship has been established, and the account of a vacation with Strickland’s family in North Carolina has run its course, Strickland vanishes. Agassi may have reasonably felt that this very sad story was Shields’s and not his to tell, but when Strickland is conspicuously inserted and the thread is dropped, it seems careless.

My biggest complaint, though, is about a style matter: though I grudgingly adjusted, I never stopped wishing Agassi and Moehringer had decided against their book-length use of present tense. For purposes of a memoir, there is no improving on good old first-person past, and any gimmicky alternative strikes me as the narrative equivalent of a waiter at a restaurant yammering on and on about the specials when I already know what I want (“Sir, I highly recommend the immediacy!”).

Nevertheless, Agassi and Moehringer ultimately are successful not only in delivering a fast, engrossing, and educational read but a model for this sort of undertaking. Literary-minded athletes of the present day, in any sport, would do well to note that this is the way to go about it: have a long and distinguished career with many ups and downs, retire, and then get a luxury-class ghostwriter and don’t hold back. A likely future classic among sports memoirs.

Tags: Andre Agassi Armin Mueller-Stahl books Brooke Shields David Strickland J.R. Moehringer Matt LeBlanc Pete Sampras Roger Federer Stefanie "Steffi" Graf Todd K

Thanks for reviewing this book. I have been a tennis and Agassi fan for years. I have wondered about this book and the very thing you said in your opening … should I read it? Now, I will.

Having read the generous excerpt that SI printed a month or so ago, and then seeing AA’s appearance on Michael Kay’s (I know, I know) interview show Centerstage, I’m willing to give Andre more credit for the prose than I would have been. He actually is unusually erudite, not only for a jock, but for one who really had no significant formal education past grammar school.

I’ve no doubt that Moehringer did yeoman’s labor with style and structure, but I no longer think this was a ghostwriting job like, say, Posh Spice’s.

I HAAAAAATE the present tense memoir. I will be relieved when that fad is over.

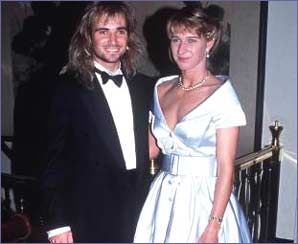

That photo above looks very much like a GEICO caveman got cleaned up for his prom date with Donna Reed.

Sorry. But that was distracting.

“strikes me as the narrative equivalent of a waiter at a restaurant yammering on and on about the specials when I already know what I want ”

Yes yes yesyesyes. NICEly put!

Jaybird – HEE!!!

Actually, Agassi has been very open about the fact that all the prose is, in fact, ghostwriting. Moehringer wrote the entire thing based on long interviews with Agassi. According to Agassi’s own accounts, he wrote none of it; he just sat for the interviews.

Great review; I look forward to reading this!

Also, I agree with the frustration of present-tense. I can only think of a handful of books (of any genre) where I actually enjoyed it. It makes me feel like the main character is stopping to tell me what s/he is doing when s/he should just be doing it.

I have been somewhat intrigued by this book and was considering reading it, but man, that present tense thing… I didn’t know about that. It may stop me from picking this book up.

Please tell me that’s not their wedding photo.

No; that photo almost certainly is from their first face-to-face meeting, nine years before the wedding. As I wrote to Sars, I believe it was taken at the 1992 Wimbledon Ball, which is covered on page 166 of the book. There had been a tradition of the just-crowned men’s and women’s champions sharing a dance, and Agassi was looking forward to this because he had had a crush on Graf for a while. But ’92 turned out to be the year they did away with the dance — the players in previous years had found it a drag. All he got was an introduction, and Graf didn’t give him much back when he tried to talk to her. Her thaw came much later. So if you look at that picture and think Agassi appears considerably more enthusiastic than Graf does about posing for it, you’re not reading too much into it.

That event was also, according to Agassi, the first time he had ever worn black tie. You can kind of tell that too.

By the way, you all have Sars to thank for finding that (I only hunted down the “Friends” one, because I wanted the hand-licking scene to be near that part of the review). I cracked up when I saw it — another example of how early-1990s hair and fashions have become as museum-worthy as those of the 70s and 80s. Where does the time go?

@Jaybird: I’m surprised at you: Agassi looks nothing like Donna Reed in that picture ;)

I thought it was great–the best sports book I’ve ever read. Moehringer’s memoir, The Tender Bar, is fantastic. I also found it totally endearing that Andre Agassi apparently believes that Steffi Graf is the most beautiful woman in the world.